📰 Harry Markowitz

https://www.ft.com/content/2ebd7d96-c3e3-4b69-92ac-e39bc90e8068

Harry Markowitz, economist, 1927-2023

He sparked a revolution in the way financial markets are understood

Alexandra Scaggs

JULY 1 2023

The study of finance can easily be split into two eras: before and after Harry Markowitz.

The economist, who died on June 22, was one of the first academics to introduce abstract mathematical concepts - and rigour - to investment decision-making. In doing so, he sparked a revolution in the way financial markets are understood.

“Everyone knew about diversification - not putting all your eggs in one basket,” said Andrew Lo, professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and co-author of In Pursuit of the Perfect Portfolio. “But Markowitz told us more than that. He told us how many eggs we should put in the different baskets, and how to diversify in a systematic way.”

Markowitz had a key insight as he read that stock prices are the present value of future dividends. That definition failed to account for uncertainty, he realised; in reality, stocks could only be valued by their expected dividends. That thought grew into his PhD thesis, where he modelled the optimisation of investments across an entire portfolio.

This development caught on widely. Almost all modern professional investing is built on this type of quantitative analysis, with a focus on optimisation and concepts of risk management that may not exist in their current forms without Markowitz.

His innovation also helped create the trillion-dollar passive-investing behemoths such as Vanguard, and in the process displaced a cadre of fund managers and stockpickers who relied primarily on corporate fundamentals and received wisdom to manage money.

Markowitz’s work was built upon by William Sharpe, who invented the standard for modelling and measuring risk-adjusted returns. Sharpe, Markowitz and Merton Miller won the Nobel Prize for Economics in 1990. “Without Harry’s work, there was no way I would have gone down that path,” Sharpe said.

Markowitz, born in 1927 in Chicago, was the only child of Morris and Mildred, who owned a grocery shop. He said they always had enough to eat, despite the Depression. He first studied liberal arts at the University of Chicago and then turned to economics for his MA and PhD. He learnt from Milton Friedman, Leonard Savage and Tjalling Koopmans. He said Koopmans’ course on activity analysis was “a crucial part” of his education, as it defined efficiency and provided a framework to analyse efficient sets.

After Chicago he mixed academic and corporate work. Sharpe and Markowitz first met at the RAND Corporation in the late 1950s, where Sharpe worked while completing his PhD. “I was very much formed by the RAND Corporation,” said Sharpe. Markowitz also studied operations at RAND, another realm that has benefited from the real-world application of mathematical theories.

Rob Arnott, founder of Research Affiliates, felt Markowitz’s influence from the start of his career. In his first job at The Boston Company in 1977 he used the economist’s algorithm in a quadratic programming optimiser, he said. He has since built a systematic investing empire, managing about $130bn worldwide.

“He knew that he changed the finance world beyond recognition,” Arnott said. “Before Harry, investing was a bunch of rules of thumb…When somebody of his phenomenal stature dies, it’s easy to portray him as an intellectual giant because he was. But he was also a kind, gentle and fun-loving person.”

Many friends and colleagues spoke of Markowitz’s irreverent humour and open-mindedness. His distaste for received wisdom and intellectual rigour may have helped him radically alter the status quo in financial markets, they say. It’s rare for a mathematician to see their work have such a widespread impact within their lifetime. But the transition to systematic and passive investing didn’t go unchallenged.

“The industry was slower to embrace these ideas…[Markowitz and Sharpe] were certainly iconoclastic, but more importantly they threatened the livelihoods of the stockbrokers and the gunslingers who were charging fairly high fees, in some cases upwards of 5 to 10 per cent for their services,” said Lo.

But Markowitz was not an evangelist for passive management or systematic investing, however. He felt that quantitative strategies were only as good as the thinkers that built them, said Arnott.

“He was a patient, gentle man, but he wasn’t patient with wilful stupidity,” Arnott said. “If your inputs are carelessly crafted, optimisation becomes garbage-in, garbage-out. He was always fascinated when people just threw numbers into a formula without carefully thinking through.”

Ethan Wu and Alexandra Scaggs

JULY 6 2023

This is an audio transcript of the Unhedged podcast episode: ‘Harry Markowitz found a free lunch in finance’.

Ethan Wu - A few weeks ago, we lost a titan of modern finance. Harry Markowitz - academic, 1990 Economics Nobel Prize winner - passed away on June 22nd, and his legacy in some ways defines modern finance. There’s no way to think about any of the concepts we use to discuss finance and markets without talking at least a little bit about Harry Markowitz’s contributions.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

So, you know, it’s a Thursday, it’s after July 4th; we thought it’d be a good time to step back into the annals of history, ask what did Harry Markowitz do and why does he matter today?

This is Unhedged, the markets and finance show from the Financial Times and Pushkin. I am reporter Ethan Wu joined today in the New York studio by Alphaville reporter Alex Scaggs, who has just emerged from the dusty tomes of the academic financial literature to talk to other human beings.

Alex Scaggs - Yeah, it’s very exciting to just like be with a person again, you know?

Ethan Wu - When’s the last time you saw another human face and not a book? (Laughter) No, in all seriousness…

Alex Scaggs - Oh, God.

Ethan Wu - Alex has just written a very good obituary of Harry Markowitz in the Financial Times, which you all should read and we’ll have in the show notes. But I think because Markowitz was so influential, Alex, in some ways it makes it hard to talk about because one of his main findings is about diversification, which literally everyone who has graduated high school has heard about, right? It’s like standard personal finance curriculum now. And so I think to talk about Markowitz, you need to talk about pre-Markowitz, and you kind of get at this in your piece. Like the first line is there’s a pre-Markowitz world and a post- Markowitz world. What is that pre-Markowitz world to you?

Alex Scaggs - Yeah. So the pre-Markowitz world reminds me of, you know, people take out their corporate balance sheets, they look at it, they say, oh, this one looks nice, and I’ve heard of this company and I like using their stuff. So let me have 50 per cent of my money in that and then 50 per cent in another stock just to be safe.

Ethan Wu - Yeah. Like, the way it works in my head is you’d go to the richest guy in town, who was also the stockbroker. He’d have a top hat and a cane and would own a big boat. (Alex laughs) And you’d say, hello, I’d like to invest my money. And he’d say, here’s some GE and some Ford; now go play golf. I don’t know if this is true, but it feels true.

Alex Scaggs - Exactly. I think that you’d probably talk about the stock picks on the golf course…

Ethan Wu - (Laughter) Right.

Alex Scaggs - Over like your third whisky of the day at 3pm. But, you know, it was sort of this, like, old boys club, you know, lots of conventional wisdom. And the thing is, like, it made sense, right? But it wasn’t very rigorous. There wasn’t a lot of math, or at least not high-level math involved, lots of arithmetic, you know, balance sheets and stuff. But then Markowitz came in and basically imposed pretty rigorous math and optimisation ideas on investing. And, you know, I think he said this, you know, the only free lunch basically in investing comes from diversification.

Ethan Wu - Exactly. And just to sharpen that point a bit: if you own five stocks, right, those stocks are going to give you a certain amount of return and they’re going to have a certain risk attached that, you know, they might go up, might go down. But if you expand that from 5 to 50 or 500, you can get the same or greater return for the same or less risk, right? More return, less risk - just by expanding the kind of base of investments that you’re using, because each of those individual stocks has various risks, but if they cancel out, they kind of point in opposite directions. Over a broad sweep of investments, your portfolio can do better. So that’s kind of the basic concept. But higher return, lower risk - it’s a great deal if you’re an investor.

Alex Scaggs - Yeah, and the thing is diversification was like, it sounds reasonable so people did it kind of. But Markowitz was the first guy to really model this out in sort of a sophisticated, mathematical way. He sort of showed it as almost a rule, right? And that kind of made him the first quant?

Ethan Wu - Yeah.

Alex Scaggs - Which I know is a little surprising because you think markets, you think numbers, you think everything’s quant. But really, I think before him it was this sort of like genteel, like, oh, this company seems nice. And I met their CEO last week and then after him, it, you know, a lot of optimisation strategies, a lot of math.

Ethan Wu - Yeah. And I think in some ways Markowitz’s biggest legacy came through one of his collaborators, and you tell the story a bit in your obituary, Alex, of William Sharpe, who I believe you talked to, if I’m not mistaken.

Alex Scaggs - I did. I did.

Ethan Wu - The William Sharpe.

Alex Scaggs - I was… Yes, so the William Sharpe. Basically, if you’ve invested in any fund of any kind, you probably recognise the Sharpe ratio, which is a measure of risk-adjusted return. William Sharpe is the guy who came up with that, and so he did that building off of Markowitz’s work. So he was at RAND Corporation while he was working on his PhD and one of his bosses was like, oh, you should talk to this guy, Harry Markowitz, or you should, like, check out his work. And he built on that sort of quanti foundation to come up with a formula and sort of a model that redefined finance, like, wholesale.

Ethan Wu - So, this is the idea - this is jargony, but it’s important - of the capital asset pricing model, commonly known as Capm. This is kind of Sharpe’s big innovation. And what it tells you is how do you put a price on a stock, and with some kind of basic inputs that, you know, these days you can get off Google - like, you know, what’s the prevailing interest rate; what is, like, the S&P 500 return - you can come up with a reasonable first approximation of what a stock should be worth. Again, it sounds jargony, but this is widespread even today. Half a century later, there was a recent paper that we wrote about on the Unhedged newsletter earlier this year finding that 85 per cent of major US corporate finance departments use the capital asset pricing model, use Capm, to make business decisions. It’s still widespread, and that’s directly from the pens of Sharpe and Markowitz.

Alex Scaggs - Exactly.

Ethan Wu - Was Markowitz like… what was he like as a person?

Alex Scaggs - Markowitz sounds like a really interesting guy. So I didn’t get to talk to him much, but I think he sort of like built the moulds of the, like, quant personality.

Ethan Wu - Yeah.

Alex Scaggs - Right? He was sort of irreverent, really open-minded, but also very rigorous. So like, he would hear ideas from anyone. He would talk to grad students. You know, he sort of was not into these kind of traditional hierarchies of finance and economics. And I think part of that was because he trusted his own intellect to be able to evaluate the ideas just on their merits.

Ethan Wu - Yeah.

Alex Scaggs - Like, he didn’t need to rely on that stuff. And it’s so funny because I kind of see it even today with quants.

Ethan Wu - Yeah.

Alex Scaggs - Like, he was apparently like a big wine guy, (Ethan laughs) and I know a bunch of quants who are really into wine and, like, trading wine and, like, it’s so funny to see these kinds of parallels, like, decades later.

Ethan Wu - You’ve got to use all that excess income on something.

Alex Scaggs - Yeah, exactly.

Ethan Wu - (Laughter) So, OK, enough time praising Markowitz; great man of financial history. But let’s talk about the haters, right? Any great man’s got his detractors. I think some of the criticism of him, I’m very sympathetic to and, you know, I put it in kind of two big buckets. And so, you know, one is that Markowitz, at least in his published work, maybe he personally had a different understanding. Markowitz’s published work misunderstood risk. This is one criticism you’ll hear, and I want to read just briefly from Peter L Bernstein’s 1996 investing classic, Against the Gods. He writes here, gives this little fictional story. “A group of hikers in the wilderness came upon a bridge that would greatly shorten their return to home base. Noting that the bridge was high, narrow and rickety, they fitted themselves with ropes, harnesses and other safeguards before starting across. When they reached the other side, they found a hungry mountain lion patiently awaiting their arrival. (Book page flips) I have a hunch that Markowitz, with his focus on volatility, would have been taken by surprise by that mountain lion.”

And I think what Bernstein is trying to say here is, you crossed the bridge. That’s great, good for you. You’ve improved your return or lowered your risk, but you had the whole other risk of the mountain lion waiting to eat you. And if the stock goes up and down, that’s one way of thinking about risk. But another way of thinking about it is, have you actually lost money in the market? And maybe a second criticism of Markowitz that you’ll hear is risk and return are just two dimensions. There’s this trend of factor investing where people look at 25 bajillion factors to consider a stock by. There’s more than just two dimensions to evaluate an asset on. And one investor I was speaking to yesterday made this point to me. Markowitz, you know, he conceptualised stocks as kind of a, you know, two-dimension pendulum swinging back and forth between risk on the one hand and return on the other hand. And, you know, maybe the way the stock market actually works is it’s a 75-dimension pendulum swinging in directions we can barely even conceive.

Alex Scaggs - Well, the funny thing about those guys, and they’re factor investors…

Ethan Wu - They’re factor investors.

Alex Scaggs - Yeah, right. Yeah. If you look at their performance, I don’t know how much good the other 73 directions are providing.

Ethan Wu - Right.

Alex Scaggs - You know, cause I think there is an edge to be had sometimes, but you have to be super rigorous about the inputs to these models. And I do think that still kind of fits with Markowitz’s general framework. It’s sort of the difference between, like, OK, if you like, pick the right factors, can you outperform or should you just invest in an index fund?

Ethan Wu - Yeah.

Alex Scaggs - And let it go?

Ethan Wu - And I’m glad you mentioned index funds because I think in some ways this is the biggest legacy of Markowitzian thought, which is that he set the bar really high. He said, if you can diversify across a large base of assets, you can get a pretty good return with totally manageable risk. And yeah, there are some active investors that are stock picking or doing some fancy 75D chess who can do a little better, but can they do a little bit over five years, over 10 years, over 20 years, over 40 years? It’s tough. It’s tough to clear that bar year after year after year. And, you know, the passive investing industry is just gigantic these days. And that comes directly from Markowitz.

Alex Scaggs - Oh, totally. And I think that it’s funny cause, you know, they say academics, it’s like tyranny of small differences or whatever. Like, I do think that Markowitz was set apart a little bit from the people who came after and that he thought that active managers could beat the market…

Ethan Wu - Yeah.

Alex Scaggs - Or some of them could. But I think he was the guy who introduced the idea that if you’re an active manager winning, there has to be another active manager somewhere else losing.

Ethan Wu - Yes.

Alex Scaggs - And that’s just a fact. Everyone in finance kind of knows this now, but he was sort of the guy that created the framework for people to understand that.

Ethan Wu - Picking the stockpicker is…

Alex Scaggs - Yes.

Ethan Wu - Almost as hard, if not harder, than picking the stocks.

Alex Scaggs - Exactly.

Ethan Wu - Yeah. (Laughter) And, you know, it’s such a huge departure from that pre-Markowitz world we were talking about a little bit ago of go to the richest guy in town and ask him for GE stock. These days if you’re an average individual investor, probably what you wanna do in most cases is just buy the index fund, right? Like, don’t try to overthink it.

Alex Scaggs - Yeah, exactly. And the funny thing is that, again, a lot of the haters of passive investing and even systematic investing tend to be the guys who think like, oh, those stockpicking days were so great. Like, oh yeah, those were the good old days. But the question is, like, good for who?

Ethan Wu - Yeah, good for the guy in the top hat that really wants you to buy some GE. [MUSIC PLAYING]

Alex Scaggs - (Laughter)

Ethan Wu - That’s who it’s good for. All right, Alex. We’ll be back in a moment with Long/Short. [MUSIC PLAYING] This is Long/Short, that part of the show where we go long and short one company, idea, stockbroker, financial theorist, whatever it might be, we go long one thing, short one thing. Last week, listeners, I’d beclowned myself by going long Biden’s student loan forgiveness program, (laughter) which was swiftly struck down the following day by the Supreme Court. So egg on my face for that. But today I’ve picked a nice safe short. I am short economic forecasting. So the Federal Reserve, they have these meetings. They published minutes, which, you know, like records of what happens in the meeting. Their staff had one of the most useless forecasts I’ve ever heard in my life, which is they forecast a mild recession starting later this year. But the possibility they narrowly avoid a recession is almost as likely as the mild recession baseline…

Alex Scaggs - (Laughter) Oh, God.

Ethan Wu - Which to me is equivalent of just writing a question mark.

Alex Scaggs - Yeah, yeah.

Ethan Wu - You know?

Alex Scaggs - That’s shrugging. That’s the equivalent of shrugging.

Ethan Wu - What do I do with that? Thank you, Fed economists. I’m short economic forecasting.

Alex Scaggs - You know, mine is sort of related to that, too.

Ethan Wu - OK.

Alex Scaggs - I am long Beyoncé tickets. You know, as we talked about before, they increased inflation in Sweden, which, you know, relatively small country, et cetera. But it turns out ticket prices have actually showed up in UK inflation data, too, even though the economy is much bigger. The funny thing is, of course, that the ONS will not actually tell us whether they included Beyoncé tickets in the data.

Ethan Wu - There needs to be a Beyoncé-adjusted consumer price index.

Alex Scaggs - I think so! We need transparency.

Ethan Wu - Yes. There’s a Nobel Prize waiting to be won here and it’s a mighty disappointment that no statistician is on this. All right, Alex. Thanks for being here. We’ll have you back very soon. And listeners, we’ll be back in your feed on Tuesday with another episode of Unhedged. Catch you then. [MUSIC PLAYING] Unhedged is produced by Jake Harper and edited by Brian Urstadt. Our executive producer is Jacob Goldstein. We had additional help from Topher Forhecz. Cheryl Brumley is the FT’s global head of audio. Special thanks to Laura Clarke, Alastair Mackie, John Schnaars, Eric Sandler and Jess Truglia. FT premium subscribers can get the Unhedged newsletter for free, and a 90-day free trial is available to everyone else. Just go to ft.com/unhedgedoffer. I’m Ethan Wu. Thanks for listening.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Harry Markowitz, Nobel-Winning Pioneer of Modern Portfolio Theory, Dies at 95

He overturned the traditional approach to buying stocks by examining the relationship between risk and reward.

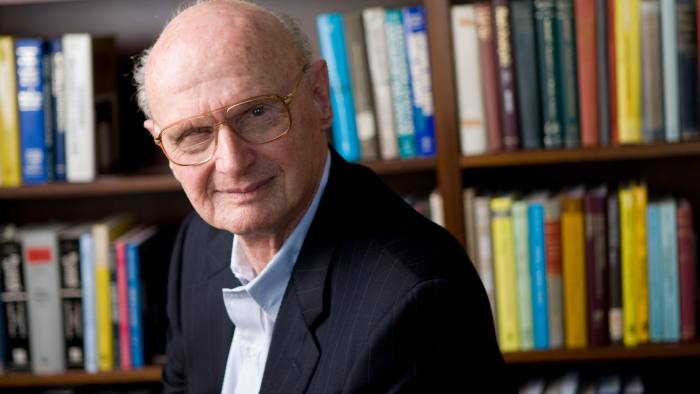

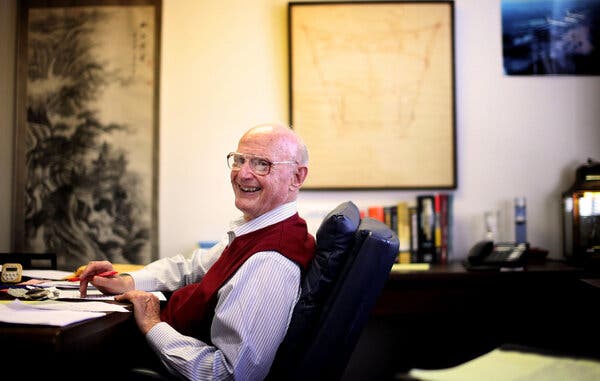

Harry M. Markowitz in 2012. His breakthrough research upended the standard thinking on investing and soon permeated all aspects of money management.

By Robert D. Hershey Jr.

Published June 25, 2023

Updated June 27, 2023, 8:54 a.m. ET

Harry M. Markowitz, an economist who launched a revolution in finance, upending traditional thinking about buying stocks and earning the Nobel in economic science in 1990 for his breakthrough, died on Thursday in San Diego. He was 95.

The death, at a hospital, was caused by pneumonia and sepsis, Mary McDonald, a longtime assistant to Dr. Markowitz, said.

Until Dr. Markowitz came along, the investment world assumed that the best stock-market strategy was simply to choose the shares of a group of companies that were thought to have the best prospects.

But in 1952, he published his dissertation, “Portfolio Selection,” which overturned this common sense approach with what became known as modern portfolio theory, widely referred to as M.P.T.

The heart of his research was grounded in the basic relationship between risk and reward. He showed that the risk in any portfolio is less dependent on the riskiness of its component stocks and other assets than how they relate to one another. It was the first time that the benefits of diversification had been codified and quantified, using advanced mathematics to calculate correlations and variations from the mean.

This breakthrough insight and its corollaries have now permeated all aspects of money management, with few professionals unfamiliar with his work.

“Modern portfolio theory has gone from the halls of academia to investment management mainstream, or from gown to town,” Robert Arnott, chairman of Research Affiliates, a large investment manager in Newport Beach, Calif., said in a videotaped interviewwith Dr. Markowitz.

When Dr. Markowitz heard one of his peers describe how his work had brought “a process” to what had been, until the 1950s, the “haphazard” creation of institutional portfolios, he knew he deserved his reputation as the father of modern portfolio theory, he said.

“That moment was one of these things where you feel a chill run up your spine,” he said. “I understood what I had started.”

In 1999, the financial newspaper Pensions & Investments named him “man of the century.”

Related work on investments led Dr. Markowitz to be regarded as a pioneer of behavioral finance, the study of how people make choices in practical situations, as in buying insurance or lottery tickets.

Recognizing that the pain of loss typically exceeds the joy of comparable gain, he found it crucial to know how a gamble is framed in terms of possible outcomes and the size of the stakes.

Dr. Markowitz won renown in two other fields. He developed “sparse matrix” techniques for solving very large mathematical optimization problems - techniques that are now standard in production software for optimization programs. And he designed and supervised the development of Simscript, which is used for programming computer simulations of systems like factories, transportation and communications networks.

In 1989 Dr. Markowitz received the John von Neumann Theory Prize from the Operations Research Society of America for his work in portfolio theory, sparse matrix techniques and Simscript.

His focus was always on applying mathematics and computers to practical problems, particularly involving business in uncertain conditions.

“I’m not a one-shot Nobel laureate - only doing one thing,” Dr. Markowitz said in an interview for this obituary in 2014. Although he was 87 at the time, he was embarked on a monumental analysis of securities risk and return.

The seminal 1952 paper, in The Journal of Finance, was expanded into his best-known work, “Portfolio Selection: Efficient Diversification of Investments,” in 1959.

Harry Max Markowitz was born on Aug. 24, 1927, in Chicago, the only child of Morris and Mildred Markowitz, who owned a small grocery store. In high school he began to read the original works of Darwin and such classical philosophers as René Descartes and David Hume. In financial terms, Hume’s work lay behind the maxim that past performance is not a guide to the future.

He continued on this track in a two-year bachelor’s program at the University of Chicago, where, inspired in part by Hume’s focus on the uncertainty of knowledge, he decided to pursue economics.

It was in graduate school, where he studied under Milton Friedman and other eminent economists, that a chance conversation on possible dissertation topics led to his work applying mathematical methods to the stock market.

The basic concepts of portfolio theory came to Dr. Markowitz one afternoon in the library while reading an investment book by the economist John Burr Williams.

Dr. Markowitz was awarded the Nobel in economic science in 1990, sharing it with Merton H. Miller and William F. Sharpe. Credit: Sandy Huffaker for The New York Times.

“Williams proposed that the value of a stock should equal the present value of its future dividends,” Dr. Markowitz wrote in a brief autobiography for the Nobel committee. “Since future dividends are uncertain, I interpreted Williams’s proposal to be to value a stock by its expected future dividends.”

But if investors were interested only in the expected values of securities, he figured, then that implied that the best, or maximized, portfolio would consist of the single most appealing stock.

“This, I knew, was not the way investors did or should act,” he concluded. “Investors diversify because they are concerned with risk as well as return.”

He set out to measure the relationships among a diverse assortment of stocks to construct the most efficient portfolio, and to chart what he called a “frontier,” where no additional return can be obtained without also increasing risk.

At the RAND Corporation, during stints in the 1950s and ’60s, Dr. Markowitz worked on practical problems in American industry that required the development of simulation methods; he created the Simscript language to reduce their programming time.

He went on to work for IBM and General Electric, where he built models of manufacturing plants. In 1962 he co-founded the California Analysis Center Incorporated, a computer-software company that would become CACI International.

Dr. Markowitz’s first two marriages, to Luella Johnson and Gloria Hardt, ended in divorce. In 1970 he married Barbara Gay. She diedin 2021.

Dr. Markowitz is survived by two children from his first marriage, Susan Ulvestad and David Markowitz; two from his second, Laurie Raskin and Steven Markowitz; his wife’s son from a previous marriage, James Marks; 13 grandchildren; and more than a dozen great-grandchildren. He lived in San Diego.

Dr. Markowitz in his office in 2012. “I’m not a one-shot Nobel laureate - only doing one thing,” he said in an interview in 2014. Credit: Sandy Huffaker for The New York Times.

In 1968 Dr. Markowitz began to manage a successful hedge fund, Arbitrage Management Company, based on M.P.T., that is believed to have been the first to engage in computerized arbitrage trading.

Dr. Markowitz was a professor at Baruch College of the City University of New York when he was awarded the Nobel in economic science, sharing it with Merton H. Miller and William F. Sharpe.

He also served on the faculties of Rutgers University, the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, the University of California at Los Angeles and finally at the Rady School of Management at the University of California, San Diego.

After submitting his landmark dissertation, Dr. Markowitz took a job at RAND and was fully confident that “I know this stuff cold” when he returned to Chicago in 1955 to defend it.

Within a few minutes, however, Professor Friedman told him that while he could find no mistakes, the topic was extremely novel. “We cannot award you a Ph.D. in economics for a dissertation that is not economics,” he said.

At this point, Dr. Markowitz recounted, “my palms began to sweat” and he was sent into a hallway, where he waited for about five minutes.

Finally, a panel member emerged and said, “Congratulations, Dr. Markowitz.” Dr. Markowitz insisted that he had not suspected the joke.

From https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/25/obituaries/harry-m-markowitz-dead.html